The one that got away

After months of searching Babs Oduwole tracked down

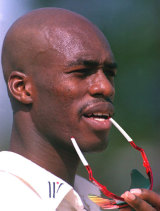

Chris Lewis, the man who might have been king

|

|

|

After six months I found him and it was not easy. I finally tracked Clairmonte Christopher Lewis down to the medieval stronghold of the Dukes of Norfolk. At Arundel Castle on June 13, before the PCA Masters v Sri Lanka Twenty20 match, six months of fruitless search came to an end. I always knew roughly where Lewis was but could never actually get hold of him. I could not speak to him nor send an email.

The search began last December, nine years after the end of a Test career illuminated by occasional shafts of brilliance. Lewis had been playing for Clifton in the Derbyshire Premier League. But Clifton's chairman Roger Jones did not know where he was. He would not be able to contact Lewis until the season started. A former first-team captain did not have a number or email either. In January a friend of Lewis's family in Australia said he often disappeared to Australia in the off-season to pro in the Melbourne league. He said he would keep an eye out. No luck there. Neil Burns, the ex-Somerset player and founder of the re-formed London County Cricket Club, said Lewis had worked with him on the Cricket Idol project. He told me to send an email which he would pass on. But the tone of the conversation indicated another brick wall. Karl Krikken, the former Derbyshire wicketkeeper, had been playing with Lewis in the local leagues. He said Ant Botha, Derbyshire's South African left-arm spinner, might know where Lewis was. No response. In the spring he turned up briefly at the ACE Academy in Slough. They considered an interview request but decided they would prefer someone able to represent ACE better. Another dead end.

It was a mystery. Where the hell was he?

Lewis had not given a full interview since 1999, when he told the ECB that a shady sports promoter had passed on the names of three well-known English players involved in match-fixing. Now, as so often before, he seemed frustratingly close but somehow beyond reach. Finally an interview was set up for a club match in June. It rained, so the PCA Masters game was a stroke of luck. At the end of the interview I jokingly said to him, "You're a hard man to find." Lewis laughed and said: "Good."

It turned out he had been in Berkshire most of the winter, coaching. He runs a programme that uses cricket to get children to keep fit, with dieticians and fitness experts on board - all very modern. "We offer more than just cricket coaching, this is the future for me." He had been travelling a bit as well. He likes to disappear.

Still Lewis seemed at ease when we finally met. He was relaxed, confident and open - which made the dogged search even harder to explain. He turned up a little before 5pm. The game was due to start at 5.30. Most of his team-mates were there a few hours before, though Vasbert Drakes arrived just before the team took the field. Wearing a T-shirt, jeans and shades wrapped round a shaven head - yes, he still favours the famed `Urban Nubian' haircut that gave him sunstroke in the Caribbean - Lewis breezed into the pavilion.

He is still in great shape. It is the first thing you notice. Walking round the ground were several old pros from Lewis's era: Gladstone Small, Simon Hughes, David Ward. They looked like retired middle-aged cricketers. Two years short of 40, Lewis looked 10 years younger.

On the day we met there had been a short interview with Lewis in The Times, part of a recent minor surge in interest. "It's just someone filling space," he says. "They're only interested in the more salacious aspects of my career still. The piece I read bore no relation to the interview I gave. In the opening paragraph, we get all the juicy bits: The Sun's `Prat without a Hat', the modelling of skinny briefs, the match-fixing allegations. Over a 14-year career it's the only bit that people are interested in."

He seemed a little hurt. Was he peeved? "It doesn't hurt," he says. "It's a bit of bore". So was he happy with what he had achieved in his career? He rocks back on his chair a little, stretches out his arms and says: "I know I could have achieved more. I say that in the context that anybody, no matter what they've achieved, feels they could actually do better. This thing with talent ...I've always had, not an argument as such, but a problem with other people who don't how you got to where you did suddenly making a judgement about your ability. They think it all comes naturally. Nothing came naturally. I worked bloody hard to get the skills I have. I remember not being able to bowl or bat. I couldn't bowl overarm until I was 12."

|

|

|

This was a surprise. Lewis always seemed blessed with the grace of natural talent. Nothing he did looked hard. He glided in to bowl with an easy, light-stepping, loose-limbed action. He still does. He ran in with the new ball at Arundel like a 28-year-old and Krikken says his bowling in the local leagues is still sharp. In the eyes of everyone else at Arundel he was bowling without strain or effort. There were genteel mutters in the crowd: "That's good pace."

How many of us knew that he could not bowl properly until he was 12, when he started playing organised cricket after moving to England from Guyana? "I look at the whole situation perhaps differently from people who look at the 21-year-old Chris Lewis and go, `My word how much talent has that boy got? He can do this. He can to that.' I actually came at it from a different point of view. I didn't see myself as somebody who came out of his mum with a pair of pads and holding a cricket ball in his hands. I actually see someone who did the work to get himself to a particular standard... [In] Guyana I played cricket before school and after school on the streets. I wasn't any good but by applying myself things became second nature ... so you make it look easy but I've worked hard for it, mate."

But only a very few Test cricketers, whatever shape they are in, will ever glide in to the crease and generate the kind of pace he does at the age of 38. "Imaginings, imaginings," he says. "I'll give you a different point of view on this. I once went up to Michael Holding - I bought into all the stuff people said about him - I said, `Mike, what's the story?' You know what he said? He said, `De thing 'ard, you know. I've got to go gym, keep myself strong, otherwise things break; nothing natural man.' That's just how people see it."

Beaming smiles and grinning with certainty, Lewis stuck to his point. He was laughing even more when told what Kevin Emery, the former Hampshire fast-medium bowler, said in the pavilion: "He ticks all the boxes of the kind of cricketer Duncan Fletcher is looking for today." Lewis continued to laugh. He certainly wished he was playing in the current era. Instead his talent blossomed in the early 1990s - now acknowledged as a mini dark age of English cricket. He wished for the rest time afforded to modern fast bowlers. So what was it like in the bad old days, the era when leading internationals played county cricket and did not rest? Would this have allowed him to do better than 1,105 Test runs at 23 and or 93 wickets at 37?

"It's hard to quantify what could have been. I can only say the environment that has gone was not necessarily the most progressive one. It was nightmare stuff sometimes. Basically you were the main man at your county; they would flog the horse before you played Test cricket. You'd finish that, report for Test cricket with no break, then they'd flog the horse. When that was done it was back to your county where they would flog you again. It was hard to be 100%. Tiredness did not get you a day off. Even if injuries meant you could not bowl, you were still fit to field or bat. Don't get me wrong I still had a great time, I enjoyed my career, I am not moaning."

Flogging aside, Chris has happy memories from county cricket. Like a lot of the old pros he misses the camaraderie. When he walked into the Arundel dressing room there was hearty back-slapping and high-fives; this for the man who shook up English cricket with claims of match-fixing and was ostracised for it. Lewis recalled the turbulent year of 1999 clearly. "People have an idea of Chris Lewis because of this. All I did was report a conversation I had with a man I was approached by [Lewis does not name him]. My story was corroborated by Stephen Fleming. The same bloke approached Fleming and offered him money to organise match-fixing. I went straight to the ECB. People still think I named people. The strange thing was that everybody I knew, as in friends, wasn't saying: `Chris, what have you done now?' They were saying: `What are they trying to put on you now?'

|

|

|

"I was naïve. If me and my manager had done our homework we'd have noticed the guy who blows the whistle gets dicked on. I'd got myself in a very precarious position. I wasn't best buddies with the ECB. I'd had run-ins with them before. I didn't want to be a whistleblower. I knew people saw Chris Lewis as a troublemaker. He was the one driving a flashy Mercedes. People would think he's consorting with these types [match-fixers]. I thought `Oh no, oh no, we can't have this.' I met my solicitor and manager. I had to go to the ECB. I was compromised once I had met these guys involved in match- fixing. I wasn't being brave. I was covering my back."

It seems there has been a huge shift in cricket and society since Lewis played. No one would pillory a cricketer for posing naked any more. Simon Jones appeared in Cosmopolitan oiled up, totally naked with only his hands covering his manhood. He won fans for it. At least Lewis had his pants on. (Perhaps if he had won the Ashes he could have taken them off.) Kevin Pietersen is Mr Bling. Blue Mohican hair goes unquestioned.

Lewis accepts that most of English cricket will always see him as mercurial and inconsistent but he believes he fulfilled his talent. "People don't see the boy who left Guyana at the age of 10 to come to England - I came to England to join my father, I grew up in Guyana with my mum - and made it to the World Cup final. My dad was a preacher man, my mum a typical immigrant mum - they wanted their children to be educated. I was never going to be that person but cricket gave me a life, one I am proud of. When I was five I saw a shooting star and made a wish. In fact I made two; one was to join my dad in England, the other to play professional cricket. Both came true. That's not bad, is it?"

Babs Oduwole is a freelance TV and print journalist