Memories of '48

|

|

|

That mood was dispelled by Bradman's 1948 Australians in a performance so brilliant and so full of character as to compel respect from the losers, and admiration from even their most devoted supporters. Character indeed; that magnificent fast-bowling pairing of the smoothly controlled master craftsman, Ray Lindwall, with the imperiously unpredictable genius, Keith Miller; the highly-talented Arthur Morris; controversial master batsman Sid Barnes; prehensile Don Tallon; underestimated but brilliantly versatile left-arm Bill Johnston. All would have been outstanding in any period; but the crowds came to see Bradman, and he devoted his immense determination to ensuring that he did not fall short of their admiration. Just as 1946 found a generation which had never seriously watched first-class cricket, so, in 1948, there were many to whom the legendary Don Bradman -- who had last been here in 1938 -- was no more than a legend. There was a point at the start of the 1946-47 series when he doubted if he would continue in Test cricket. After his success then and in the series with India of 1947-48, he announced that the Melbourne Test would be his last on Australian soil but that he was available to tour England in 1948. So, rising 40, he set out on what had to be a triumphal progress or a flop.

Lacking confidence

Traditionally Australian cricketers have matured young and retired early. So the Don, elderly in his kind, reacted uneasily to the leg-pulling of Walter Robins about his imminent eligibility for the Forty Club. For one of his salient ability, he seemed to some oddly lacking in confidence. Certainly from 1946 onwards he knew he was not the man he had been -- who could expect to be? -- but also that it was nevertheless still possible for him to be a better batsman than any contemporary. As virtually the only great cricketer who had never known failure, he understandably dreaded it. Without doubt, at any time up to that irreversible decision to come again to England, he would have retired if he sensed that his standard of performance had fallen below the level of success in Test cricket.

So to the first match of the tour, at Worcester. On his three previous tours -- in 1930 (of which he was the only survivor), 1934 (only Brown remained of that party), and 1938, his scores on that opening appearance had been 236, 206 and 258 in the only batting Australia needed of him to win. Now, after Worcestershire had made 233 and Morris and Barnes had founded the Australian innings soundly, and, on the second morning when Barnes was lbw to Dick Howorth, Bradman walked slowly out to the wicket. He played back with quite immense care to Howorth, who bowled him his faster 'arm' ball; the Don dropped on it only just in time. For half an hour he ventured little; then, all at once, he was in the old familiar stride; quick in estimation, rapid in moving to the ball, merciless in directing even the marginally inaccurate ball through the gaps in the field. He made 107 and the ground-record crowd, most of whom had come to see him, never hinted at being so locally partisan as to wish him to fall short of his hundred.

Rarely can a man have set out so certainly to command success. He played in eight of the tourists' first dozen matches -- missing those with Yorkshire, the two Universities and Hampshire -- and his scores were 107, 81 (furious with himself at falling short of the century), 146, 187, 98, 11, 43, 86, 109; 868 runs at 96.44 up to the first Test at Trent Bridge.

After early loss of play to rain, England collapsed to 74 for 8 against Miller, Lindwall and Johnston; and were lifted to the comparative respectability of 165 by Jim Laker and Alec Bedser. Barnes and Morris saw out the remaining few minutes of the day and next morning reached 73 before Morris under-edged Laker into his stumps.

|

|

|

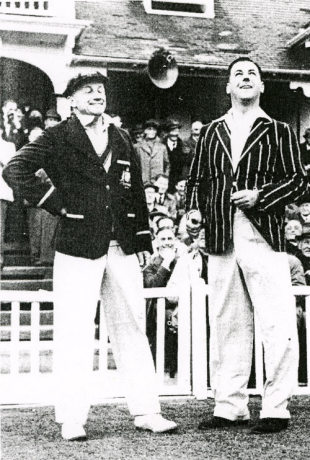

At that juncture England glimpsed opportunity: almost anything might have happened to Bradman's future, the match, even, perhaps -- though improbably -- the rubber. All at once, though, Bradman took command. Half an hour had been enough for his eye and timing to adjust and here he was, as good as ever. His baggy cap concealed his thinning hair so that he looked no older than he had done in the 'thirties; short, trim, with wide, lean shoulders, narrow hips, the slim legs, neat feet and nimble movement of a dancing master. Hungry for runs, he moved back on to his stumps or far down the pitch; his wrists were steely as ever, driving scaldingly through mid-on and mid-off, rocking back and forcing through the covers; keeping his leg-side scoring strokes safely along the ground. Norman Yardley had Brown lbw but Bradman simply went on; the unfailing master.

Hassett, Hutton, Compton, Miller, Johnston all subsequently left their impress on the match, which Australia won, capably, by eight wickets (Bradman c Hutton b Bedser 0). Folk history had been satisfied, though, on the second day, when, just before six o'clock, Don Bradman reached his century. Indeed, after the applause which celebrated the feat, a steady stream of spectators left the ground. They had come to see not a cricket match, but history -- Bradman making a century. He would not do less than satisfy them, giving them a memory to boast of in years to "come. They had seen the great batsman in his greatness.

This article first appeared in the February 1980 edition of Wisden Cricket Monthly