The indomitable spirit of Clive Rice

He wanted to play against the best and show that he was among the best, as his admirers testify

Firdose Moonda

28-Jul-2015

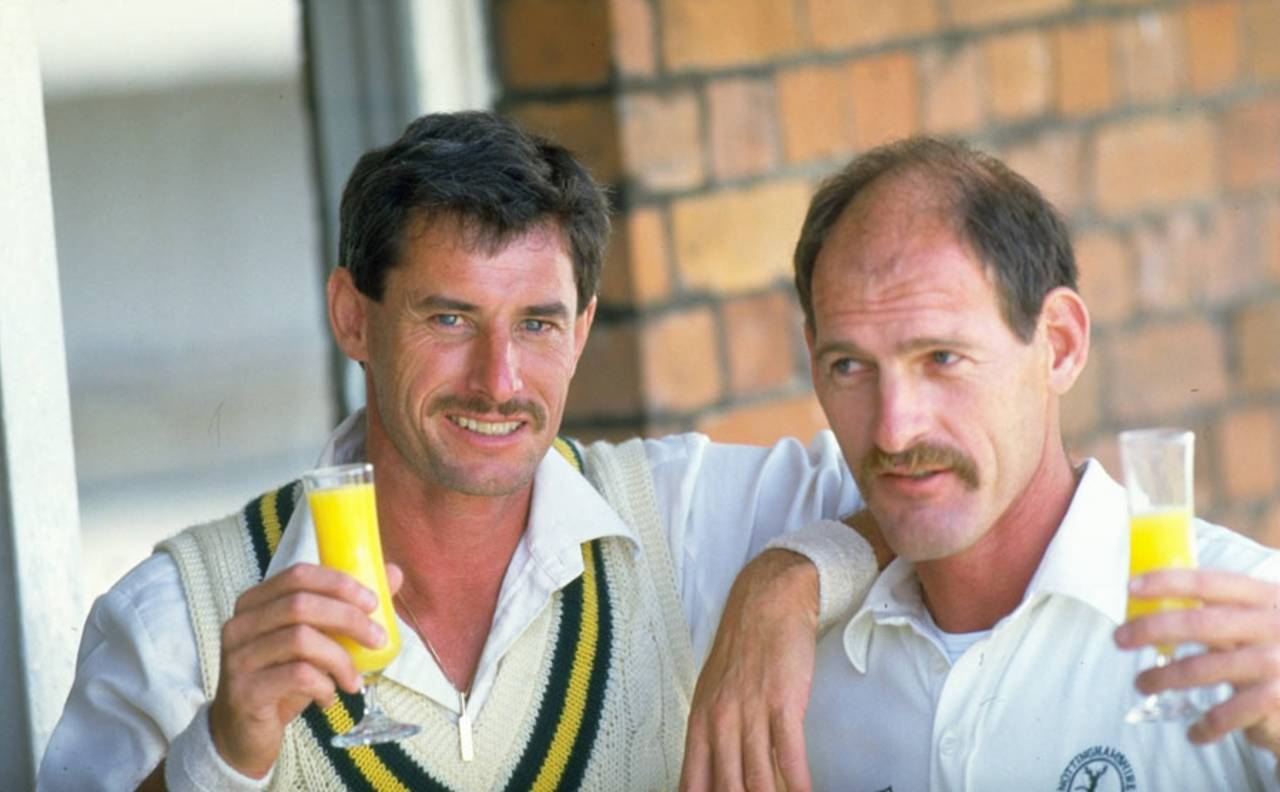

Ali Bacher believed had Clive Rice (right) played Tests, he would have been talked about in the same league as Richard Hadlee • Getty Images

Clive Rice started as a bowler but wanted to be a batsman. So he did both. In the process, he established himself as one of best allrounders the game has ever seen.

Clive Rice started playing in South Africa but wanted to play around the world. So he did both: from the mean machine in Transvaal to the English county circuit and a World Series in-between.

Clive Rice started with dreams of Test caps and a World Cup but had to settle for three ODIs, which he treasured more than any of us can understand.

"They don't come more positive than Clive Rice,"Ali Bacher told ESPNcricinfo. "He was the eternal optimist and he was determined, so he was able to make the most of everything."

Bacher would know. He captained Rice at the start of his career, and saw the impact he could make in just his third game. Transvaal were closing in on the defence of their Currie Cup title in 1970-71 but draws with Natal and Western Province stalled them. They needed a first-innings win over an intimidating Eastern Province team, which included the Pollock brothers and Tony Greig, to seal the deal. That looked unlikely when Eastern Province posted 359 in their first innings and Transvaal were 275 for 6 in reply.

"Clive came in at No. 8, in a pressure situation. We were a long way behind, they had the second new ball and it was overcast. We were worried," Bacher said. "But then he scored 52 and he shared a big partnership (147 runs) with Lee Irvine. We won on first innings, got the points and went on to win the Currie Cup. And it was in that innings that you could see the determination that Clive was all about."

I just saw a plethora of tubes. He had them everywhere. But then I looked again, and I also saw he had a cellphone in each hand. That was Clive. He kept goingAli Bacher after visiting Clive Rice at hospital last August

That summer, Bacher watched Rice's dedication turn him from an obviously skilled cricketer into an actual athlete. Rice ran rings around his team-mates and the rugby field they practiced on, adjacent to Wanderers Stadium, to introduce a new culture to cricketers. "We all had day jobs so we would get to practice at about 4.30 in the afternoon, hit a few balls, have a bowl, pack our bags and go home but he would still be there, doing 15 or 20 laps around the field," Bacher said. "He was the first person I knew who saw fitness as a prerequisite for doing well at the highest level."

Bacher retired in 1974 but became involved in administration and kept a close eye on how Rice developed, especially after he took over as captain of Transvaal. By then, Rice had experience in the World Series and had learned what he needed to do to compete against the world's best.

"He wanted to improve his batting and he wanted to improve his bowling speed and he worked really hard on both," Jimmy Cook, Rice's former Transvaal team-mate said. "At one stage he told us he wanted to bat No. 3 and I remember thinking that was a bit high. He started off No.10 when I first met him, but he could have done it. Because of the bowling load, he moved down to No. 5 and he was just phenomenal there."

At that stage, had Rice been able to play Test cricket, Bacher believed he would "be spoken about in the same league as Ian Botham or Richard Hadlee."

But Rice had to find opportunity on the county circuit instead. He played for Nottinghamshire and led them to two county championships in the 1980s. An hour's drive away, Peter Kirsten was playing for Derbyshire and maintained contact with his countryman. "He [Rice] would invite me to go and watch Notts Forest football games with Richard Hadlee. In those days, Notts Forest were European Champions and Ricey was good friends with Brian Clough, their manager."

Rubbing shoulders with international stars only increased Rice's yearning for international cricket. "He would tell me, 'Kirsy, imagine if we were playing. We would show them a thing or two," Kirsten remembered. All Rice could do was transfer that self-confidence onto the domestic game.

He turned the Transvaal team into what Bacher called an "invincible force," that other teams "could not even come close to beating." He led them by example, with community values at the core - Cook remembered how they "travelled together, toured together, did everything together, like a big family," and with a ruthlessness that was unrelenting.

Peter Kirsten on Clive Rice: He would tell me, 'Kirsy, imagine if we were playing. We would show them a thing or two'•Getty Images

Before the 1987-88 Currie Cup final against Orange Free State, Rice gathered his men for a team talk that summed up his faith in their strength. "He looked out over the Wanderers and said to us, 'I've looked at their team sheet and I've looked at our team sheet and they have no chance of beating us.": And that was that. Transvaal promptly won their eighth title in ten seasons.

While all that was going on, a young batsman named Andrew Hudson was starting out in Durban and had Rice as "one of my role models." Hudson never dreamed he'd one day have the opportunity to play with his idol. But as Rice's career wound down, he moved to the coast and played for Natal, where he was a mentor to Hudson, Shaun Pollock and Lance Klusener.

"He was direct, he was no-nonsense, he was straightforward and he always spoke his mind," Hudson said. "You knew where you stood with him."

And Hudson stood on very solid ground. Rice "backed" him, so much so that Hudson believed he has Rice to thank for the opportunity to tour with the South African team when it finally came.

In 1991, South Africa were welcomed back to international cricket and Rice, though "past his best," as Bacher put it, led them to India. There, Rice's big character was apparent to all when he felt small standing next to a woman barely an inch above five foot. "I remember when we met Mother Teresa - he kept saying he couldn't believe how little she was," Hudson said.

Those three ODIs were the pinnacle for Rice even though he wanted so much more from the game he gave everything to. "It was a special moment but I don't think it made up for the sadness that he did not get to play to Test cricket," Hudson said.

A year later, Rice missed out on the World Cup and so did Cook: "We were very disappointed. We were both fit and very determined."

Although Hudson believed Rice would have played on "for as long as he could," his contribution to South African cricket ended there.

He managed a South African academy side in 1992 but his coaching took him back to Nottinghamshire, where he enticed Kevin Pietersen years later. "I don't think he [Rice] was able to give South African cricket too much after he retired and that's a pity," Kirsten said.

Rice remained on the fringes of South African cricket's conscience until he took ill last July. A month later, Bacher went to visit him in intensive care. "When I walked into his room, I just saw a plethora of tubes. He had them everywhere. But then I looked again, and I also saw he had a cellphone in each hand. That was Clive. He kept going."

And Rice intended to keep going. Earlier this year, he had surgery in India and his former team-mates believed he was recovering well. Kevin McKenzie had lunch with him on Sunday, two days before he died and told Cook he thought Rice was "doing well."

Rice would likely not have had it any other way. Remember, he started off believing anything was possible. By all accounts, he finished that way too.

Firdose Moonda is ESPNcricinfo's South Africa correspondent