Bearded giant

On his 150th birth anniversary, we remember the man who found cricket a country pastime and left it a national institution

EW Swanton

29-Oct-2008

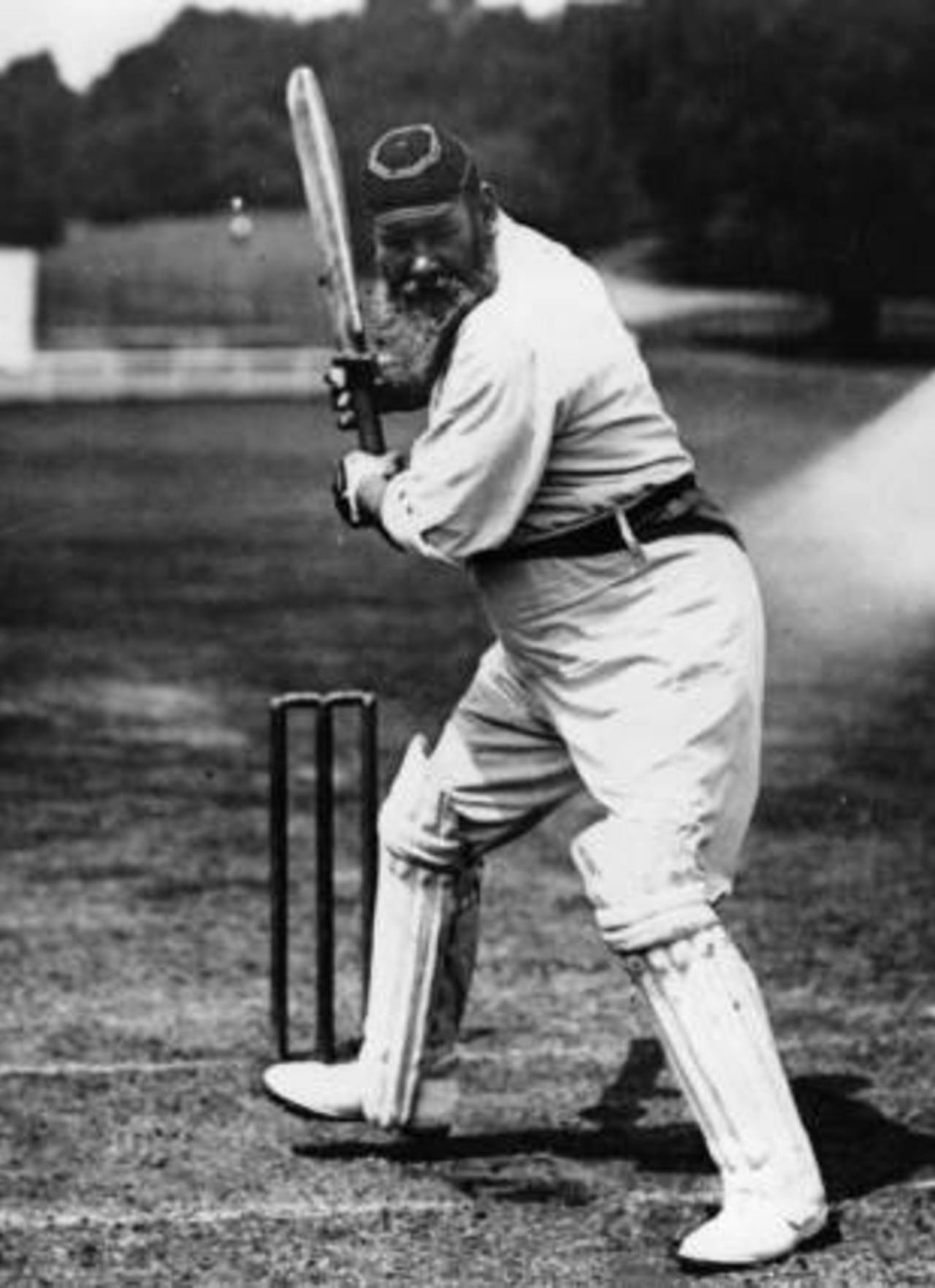

WG Grace's stamina, energy and combative spirit were extraordinary from youth to old age • Getty Images

Dr Henry Mills Grace had a country practice outside Bristol. In 1831 he married Martha Pocock and they had eight children, four of each. A busy man, he loved cricket, taught his boys to play and had the chief

hand in founding the Gloucestershire County Club. The last but one child was William Gilbert, known to the family as Gilbert and to the world to this day, though he has been dead 80 years and more, as WG.

Born on July 18, 1848, W G's early adulthood coincided with a country-wide explosion of interest in games. The railways had arrived to bring to the cities the pastime which had been popular for centuries in the villages of southern England. In London the Marylebone Cricket Club had had their headquarters at Thomas Lord's ground in St John's Wood since the year of Waterloo. What was needed was a focal figure, and if ever the hour produced the man it did so in this tall, strapping young Gloucestershireman.

His preponderance as a batsman came astonishingly quickly. Gentlemen v Players, Amateurs v Professionals, were the great matches of the year. He played first against the Players at 17, and the Gents won for the first time in 19 years. Thereafter, for many summers, they scarcely lost. When he was 23, on those still rough pitches, W G scored 2,739 runs, a figure unapproached for 25 years. His batting average, 78, was twice that of the next man.

I must content myself with the two high peaks of his career, each testimony to his amazing stamina.

In 1876 he made, in 10 days, 839 runs: 344 v Kent at Canterbury (then the highest score), 177 at Clifton against Notts, and finally, what he rated as his best innings, 318 not out at Cheltenham against Yorkshire. Don't forget all the travel, by train and horse-drawn cab and maybe pony and trap.

Then, a veteran coming up to his 47th birthday, he scored 1,000 runs in May 1895, never done before and only twice since, including his 100th hundred. No one else had made as many as 50. Seizing the public

mood, the Daily Telegraph raised £5,000 in shillings, MCC over £2,000. There never was such a hero: not even, I think, Don Bradman. Physically so unalike, these two men at the peak of cricket fame had two qualities in common: great determination and great strength of character.

I have perhaps one credential for celebrating this 150th anniversary, for my father was treasurer of Forest Hill Cricket Club, where WG made one of the last of his hundreds, 140 to be exact, in July 1907 for London County. My mother helped to preside over the tea pavilion, and I'm sure she would have had me, her six-month-old baby, with her.

The Old Man managed and led London County for a decade or so into the new century, living in Lawrie Park Road, Sydenham, just round the corner from my parent's house some years later.

Fifty-nine in July 1907, W G carried a lot of weight, but his energy and appetite for cricket and other games were undiminished - he made a thousand runs and took a hundred wickets in club cricket that year. He

was a founder of the Bowls Association, and in 1903 at Crystal Palace had captained England against Scotland in the first of all international bowls matches. He had also, when over 50, taken up golf

with enthusiasm, as recorded by Bernard Darwin, who played with him in foursomes at Walton Heath. Ever a keen competitor, Darwin records his playing at Rye with his old Australian crony, Billy Murdoch. They had

both been in some trouble when Murdoch called out: "I've played five". WG: "I've played two less than you."

In his charming memoir Darwin wrote: "He must always be doing something, preferably out of doors, and in the nature of a game or a sport." From youth, he had embraced all the country pastimes. He was a

good shot and a skilful fisherman. Though he became too heavy to ride a horse he followed the beagles until he could no longer run. In a London ice-rink, when about 60, he took up curling. His stamina and energy and combative spirit were extraordinary from youth to old age.

It happened that as a young man I played cricket with quite a few who had played with him. Young cricketers of his latter years - and he always encouraged the young - were in the late 1920s only in their

40s. Cricketers went on playing a lot longer then than now, and I can see some of them still, their trousers held up by the red-and-yellow sashes of MCC: Bell, Slater, Grierson, Beaton, Colman, Bridger: names

long forgotten. They all talked to me about W G, and they all spoke of him with great affection. So did CB Fry when he and I wrote for the Evening Standard in the 1930s. WG came across as a spontaneous,

cheerful and wonderfully modest companion. Indeed there seems not to be anyone who knew him who was not devoted.

From youth, he had embraced all the country pastimes. He was a good shot and a skilful fisherman. Though he became too heavy to ride a horse he followed the beagles until he could no longer run. In a London ice-rink, when about 60, he took up curling

I underline this fondness and esteem because some of the writing leading up to this anniversary has been curiously ambivalent and in the case of an article in the current Wisden positively disparaging in

parts. Geoffrey Moorhouse, the author, concludes there was "not that much to Grace" apart from his skills and his devotion to his family and "one might identify Grace as suburban man incarnate". To categorise WG as suburban in heart or mentality, in the common understanding of the term, is a ludicrous assessment. It contradicts Darwin, Clifford Bax, HS Altham, AA Thomson and other reputable biographers who all stress that by birth and upbringing, and in his love of open-air pursuits, he was every inch a countryman.

AS to there being "not that much" about him outside his cricket, Sydney Pardon, the great editor of Wisden, in his obituary notice in the 1916 edition, painted a rather different picture: "Personally, WG struck me as the most natural and unspoilt of men. Whenever and wherever one met him he was always the same. There was not the smallest trace of affectation about him. If anything annoyed him he was quick to show anger, but his little outbursts were soon over. One word I will add. No man who ever won such worldwide fame could have been more modest in speaking of his own doings." That is surely a fair assessment from Pardon, the prince of critics. Note the quick temper and its equally quick recovery. "Won't have it, can't have it, shan't have it," he once exploded. He and his hot-headed brother EM, the coroner, were no paragons, but the stories of WG stretching the conventions of the game, indeed at times the laws, concerned the exhibition matches, the benefit games for professionals, wherein he was the star attraction, the one all had come to see. He was a way apart from the public school amateur trained to curb his emotions. The crowds loved his robust spirit.

They also loved the full beard he wore from his youth. Beards, it seems, had become popular in the Crimean War, to keep out the cold. Bax wrote: "There is no more renowned beard in all humanity". It helped to make him the best-known man in England after another bearded figure, the Prince of Wales, later Edward VII. At the recent opening of the WG Grace Exhibition at Lord's one of the eight Grace descendants, his 93-year-old granddaughter, Mrs Primrose Worthington, told us how as little girls she and her sister were allowed to plait the famous beard, sitting on his knee.

Was he truly an amateur? In that he was openly paid for playing, the answer is a clear no. The fact is he had a status of his own, accepted by all and in particular by the MCC, who shrewdly elected him a member

when he was 20 and indeed raised their first testimonial for him before he was 30. At the time MCC's authority in the game was under threat from the professionals. If he had joined them, who knows? There

he was, on the one hand studying to be a doctor at the Bristol Medical School, intending to follow his father and three elder brothers in the profession. On the other hand, the game was poised to spread rapidly

far and wide. It was about to be lifted on his broad shoulders to unimagined heights of public popularity.

WG Grace with the Prince of Wales around 1908•PA Photos

For a decade, medicine took second place to cricket. However, in 1879, following an intense period at St Bartholomew's Hospital, the wretched exams were passed. And when, the following year, the first home Test

was staged at the Oval, the first English hundred (152 to be precise) was scored by Dr WG Grace MRCS, LRCP.

A word about his doctoring: he became the parish doctor of a mostly poor district of Bristol, and for 20 years devoted himself wholly to his practice in autumn and winter. To help him out in the cricket season he employed not one locum but two. He sat up all night with a woman he had promised to see through her confinement - and made 221 not out at Clifton against Middlesex next day. At Christmas, up to 100

of his patients brought two pudding basins to be filled with roast beef and plum pudding. He was kindness itself to the poor and the young, the well-loved father of the parish. This busiest phase of his life ended when some official re-arrangement of the boundaries led to his improving his financial security by accepting the managership of the new London County Cricket Club.

In that June of 1899, aged 51, he played his last Test against Australia. He now gave all his energies to the London County experiment and actually, 41 years after his first encounter with the Players, played just once more - it was the 85th time - for the Gentlemen against them. In an atmosphere of such euphoria as may be

imagined and on his 58th birthday he made 74. Until he tired, they said, his batting was like old times.

The last the public heard from WG was a letter to the press in August 1914, a few weeks after the outbreak of war, appealing to all cricketers to come to the aid of their country in its hour of need. With two sons serving - Edgar was to become an admiral - he found the slaughter of youth on the Western Front agonising. In October the following year came the stroke from which he quickly died. His epitaph can be written in the well-worn phrase: he found cricket a country pastime and left it a national institution.