Tough love and love-ins

Peter English

03-Aug-2005

A lot has changed in the Australian dressing rooms over the past 30 years. New players once had to endure initiations that were far worse than anything they experienced on the field. However, today's debutants are products of the new school

|

|

|

Dressing rooms feel like second homes for players snug in the group ethos and safe under the side's rulers. Offering protection from the middle, the mugs and the autograph hunters, it is designed as a mates-only sanctuary. Beers and bonding at stumps with tall, tinkered and tatty tales in between. Australia's first-class teams are part of the country's most exclusive clubs, an almost mythical place of joie de vivre with access restrictions making the Top End's coastline seem porous.

Inside the alpha males flex and bluff, but the rooms also see men at their most naked, angry, petty and vulnerable. They are delicate, insecure, powerful and often mean places that can accept new members unconditionally. Or ruthlessly turn on or abandon them. For players on the edge - fighting for spots, battling personalities or confronting the junior-senior hierarchy - the horrors of the experience can remain decades after they have been pushed down the pavilion steps.

Like the national broadcaster with its "every one's ABC" slogan, Australia's dressing room holds a feeling of public affection and ownership, even if it is not sure what goes on. Ideally, it is an organisation with members working together to reflect the nation's values while producing outstanding quality. Both funded-by-the-masses programs are sites for infighting, ostracism, mocking and bullying that has severely disrupted and ended careers.

Greg Matthews arrived full of enthusiasm for his first Test and was so excited he told the papers he'd happily play for free. Greg Chappell ripped up Matthews's cheque and his emotion was surprise as he returned to his seat to finish his beer. "In the Australian team back then it was very classist and elitist," he says. "You were expected to sit in the corner. Yes sir, no sir, three bags full sir. I didn't rebel against my peers, I copped it." Matthews reckons he could have played 80 Tests, but finished on 33.

The early 1970s legspinner John Watkins retired from first-class cricket after a disastrous West Indies tour that still forces head shakes from the tourists. Watkins's one-Test career in 1972-73 produced no wickets, a lifetime of nightmares and pushed him further towards life as a recluse. Scott Muller's international days closed with "can't bowl, can't throw" and he's so upset by the incident he won't discuss it. Four words are remembered more clearly than any of his seven wickets.

Denouncing the dressing room almost feels illegal. Whenever the camera pans from the middle to the seated areas at the SCG or Adelaide Oval they look such happy places. The upbeat, in-joke atmosphere is usually described in ghosted autobiographies: Darren Lehmann insisted it was the inner sanctum. "It's not a million miles from the classroom," says Damien Fleming, "but there's no teacher to stop all the funny comments." Fleming enjoyed his seven years in and around the national set-up far more than his seasons in the disrupted Victoria corridors. Michael Kasprowicz, part of the smiling four-man fast bowler's cartel, says Australian rooms have always been fun. However, each player remembers his early treatment that varies from blokey humour and nipple cripples to dumping a debutant's kitbag into an unflushed toilet or forcing a pair of spikes into the 12th man's chest for cleaning.

Sheffield Shield changing areas were at their toughest in the 1970s and 80s and the attitudes and behaviour were promoted to the national team. As a Brisbane schoolboy, Kasprowicz swapped his uniform for playing gear outside the Gabba dressing room. "These days it's a lot easier for young guys," he says. "When you come into a new team you're already under a lot of pressure. They come into a pretty good environment and I'd like to think the senior guys help it out. In the late 80s there was a pressure to fit the mould."

Fleming's first steps came at a time when new faces were made to feel as uncomfortable as possible; Ray Bright, the Victoria captain, told Colin Miller to sit his opening game under the stairs. Light-hearted initiation ceremonies were genuine ways to make someone feel welcome, but the fickle outlook could change to lasting punishment for such trivial matters as sitting in the spot of a long-term member.

The current Australian cult chants the victory song `Beneath the Southern Cross' and happy-claps en masse for every milestone. Individualism is celebrated and this "new school" is so attractive that players cut from the circle of trust are desperate to return. "My set up is about everyone being able to grow so nobody seems to be different," says John Buchanan, the coach since 1999. "It's not only the junior players, but also the senior players, who should not be isolated or ignored. Everyone should have equal responsibility." Rites of passage now include the official presentation of a baggy green cap and simple unofficial ones such as being invited to a seat closer to the showers than the door.

|

|

|

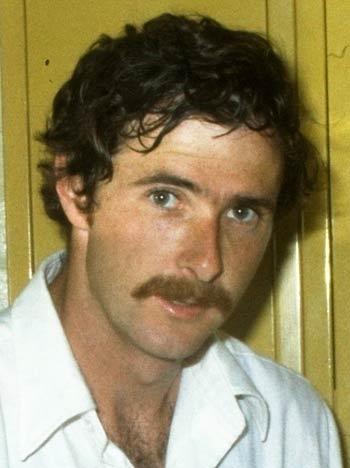

Quirkiness, too, has only recently become appreciated. Conformity was never mentioned in the coaching manuals, but until Australia became world champions it should have sat beside front-foot defence. The old schools of the 1970s operated in the tough, romanticised and moustachioed days of flared tempers and trousers; the era of sledging, physical presence and sweaty pressure that began under Ian Chappell and judged a bloke by the length of time he stayed in the dressing room. Individuals were belittled if they didn't imbibe the spirit set for so long by Marsh, Lillee and the Chappells. Newcomers had to prove they were worthy of the cap. Being dropped could come as a relief at the reprieve from boarding-school treatment.

The senior-player judiciary classed Max Walker and Kerry O'Keeffe as club bowlers; Graham Yallop was targeted because he'd replaced the popular Rick McCosker; Watkins was patronised in the primary-school sandpit belief that he would fit in; and a talented batsman was held down by team-mates while another farted in his face. One bowler who spent almost a decade in the Test side with Lillee shared only "three or four" sentences with him. Conscientious trainers wanting more time in the nets were jeered for not sharing beers.

Yallop, who admits his selection against West Indies in 1975-76 "put a couple of noses out of joint", says those rooms had the ability to push individuals away. "I didn't make a note of the shunned people," Yallop says. "It was an odd situation and it was a minority. It didn't happen when I was captain, I wanted to make everyone feel welcome, particularly after what I'd gone through coming into the side at the age of 23."

Including a 48-Test stint as Australia's captain, Greg Chappell sat in national dressing rooms from 1970-71 to 1983-84 and defends the treatment as "tough love". To the players spat out for short times or forever it was disrespect. "It was tough love, that was the era," he says. "Thankfully we've moved on."

A 24-year-old offspinning allrounder is glowing after combining a hard-earned 75 with four wickets on debut. The playing glare of the 1983-84 Boxing Day Test and the persistence of Abdul Qadir, Sarfraz Nawaz and Zaheer Abbas were conquered. Despite an altercation with a gateman when forgetting his player pass, a fledgling career looks ready to boom. Better still, at the end-of-match dressing-room roll call he is picked by Greg Chappell to receive his first cheque.

"Chappell put his arms around me and looked at me from his 6ft 3in," says Greg Matthews. "Wow, I'd got runs and wickets, and now praise from `God'. Then Chappell said, `I read in the paper you'd play for Australia for free', and he ripped up my cheque. I was shocked." Already fined a whopping $1000 for the turnstiles incident, - he did a lap of the ground because he couldn't find the player entrance and, being passed from official to official, jumped the barriers and had his jacket ripped when grabbed by the gateman - Bob Merriman, the manager and current Cricket Australia chairman, halved his punishment. Matthews maintains it cost him $500 to play that game.

The memory has slipped from Chappell's mind, but with his sense of humour he says it wouldn't have surprised him. "I do recall having a beer with Matthews, Lillee, Marsh and the manager at the Melbourne Hilton," he says. "It was part of the environment; the new boy was on the end of practical jokes."

David Gilbert, Matthews's New South Wales team-mate, vividly recalls his first-class debut for New South Wales against Pakistan in 1983-84. Selected the night before, he was edgy as he arrived at the SCG early and "foolishly made a fatal mistake" by dropping his bag in before running some laps.

|

|

|

"Going back to the rooms I passed John Dyson," Gilbert says. "There was a hint of a shoulder and he said, "If you want your kit it's down the toilet." Unknown to Gilbert or his bag, it was resting where Dyson had sat for seven years. Gilbert retrieved it from the used bowl. "It's such a vivid memory," he says. "I couldn't believe it would happen to someone on debut, it was appalling. John and I became good friends but it was a bizarre initiation. There were no favours, it was like a boarding school."

The open-chested atmosphere of a decade earlier took John Watkins, a talented but fragile legspinner, as its biggest casualty. When Watkins, 29, was picked for an SCG Test against Pakistan he had already been chosen for the following West Indies tour alongside Terry Jenner and Kerry O'Keeffe. Incredibly nervous, insecure and already out of favour with the men close to Jenner, he bowled six eight-ball overs of long-hops, full tosses and wides. "I had a bad Test and couldn't really handle it," says Watkins. In the West Indies the senior players turned on him; his Test career was already over. A team-mate says he "bowled like Shane Warne" in training, but sprayed the ball knowing how poorly he was rated by Ian Chappell, the captain, and Rod Marsh.

Landing back in Sydney, Watkins retired and returned to Newcastle, where he played mainly as a grade batsman and resumed his shipping and tugboat career. "If you have to contend with that sort of backbiting it's not worth going on tour," he says. "I was happy to get home and I could've done with some more moral support. I don't know what they were saying behind my back." It was awful. There was little doubt that he wasn't up to Test standard, but his simple upbringing was attacked with regular and nasty tricks, and his team-mates fanned his fears of the West Indies.

Now 62, Watkins speaks quickly and wants the conversation finished. He says the treatment didn't hurt or bother him. Life-long friend Ken Clifford says Watkins "is almost a recluse because of it". "John Benaud was the most helpful," Watkins says. "Ian Chappell has some mug in him. The story could be exaggerated - I cop it sweet."

Matthews refused to be so deferential and would not consider walking away. He asked Kim Hughes, his captain, where he could sit before taking a spot near the door in his first Test, which was the penultimate match for Marsh, Chappell and Lillee. Later he would have stand-up arguments with his captain Allan Border. Matthews and Border have since grown up and made up. "AB probably cost me 50 Tests and hundreds of thousands of dollars," Matthews says, "but that really doesn't matter because we get on really well now."

Talked at instead of talked to, Matthews was isolated by players and management on the 1983-84 West Indies and 1985 Ashes tours. "I was offered $200,000 to go to South Africa, but I didn't take it even though I was being ostracised," he says. "I didn't want to be banned because I wanted to play for New South Wales for 10 years, and Australia."

Matthews says he survived the treatment and forced the selectors into re-picking him because he'd been taught by his mother to be true to himself. "Up until there were 15 Tests a year I had the record as the most dropped player," he says. "I knew I was up against it and just had to realise two plus two equalled five. I was a working-class cricketer who wasn't intimidated, but people burnt me." Cocooned from the dressing room, he averaged 41 with the bat - the same as Mark Waugh - but with his team-mates around him in the field he managed 61 wickets at 48.

Bob Simpson spent five decades in Australian dressing rooms from the 1950s as a player, captain and coach, and was in charge during two-third of Matthews's Test career. "There have got to be ground rules set for everyone with no basis for special treatment," he says. "There should be no favours for different or difficult people. You have to treat them as grown men and expect them to act like grown men."

Gilbert was subjected to a different pressure to Matthews on the 1985 England tour when the tension and suspicion of the South Africa rebels turned it in "a disillusioning experience". Players revolved like hotel entrances and Gilbert says the bunch of young guys was too green to consider naughty or mean pranks. It helped create chinks in the stranglehold.

The New South Wales chief executive and former coach of Surrey, Gilbert says the attitude had to change. "You couldn't continue those archaic ways to earn your spurs," he says. "In first-class cricket everyone is there on merit and deserves respect." Gilbert's belief is confirmed by his most memorable action during his stint with Surrey, where he tore down The Oval's dressing-room wall between the capped and uncapped players.

|

|

|

While Matthews and Gilbert struggled as new kids, Geoff Marsh, who was on his way to the national vice-captaincy and Australia's head-coaching position, was prepared to follow the road rules and sit, look and listen. "You had to learn the code," he says. "It was a tough and fair school in Western Australia with Lillee, Marsh, Inverarity and Wood. There was protocol: don't jump in the seat DK has sat in for 15 years."

In one of his early games for Western Australia, Marsh stood up to have a shower and Rod Marsh asked him why he was undressing. "Don't you want to learn about cricket?" he asked. Hearing the opening batsman's yes, Marsh told his namesake to grab a couple of king browns from the fridge and sit down next to Greg Chappell. Cricket was talked and talked.

From the benches next to the Gabba dogtrack to a seat below the Adelaide Oval honour board where century makers are misspelt centurians, dressing rooms were a haven for Chappell. Under his captaincy, entry for non-team members was heavily restricted and he wanted a relaxed mood. The 12th man was the waiter and if there was a need for punishment the senior players kept him back by boozing for a couple more hours. "Young guys were seen and not heard," he says.

By the end of Chappell's international career he says newcomers were encouraged and welcomed. Matthews disagrees, but Chappell points at the peer-based structure of the period with an absence of support staff. "We helped where we could, but there were times when junior players were held on the outer because of their personality more than anything," he says. "You learnt a lot from listening, some went with the flow, others were left in the cold. They were the minority."

Darwin didn't become a Test venue until 2003, but the scientist's survival-of-the-fittest theory was working in Australian dressing rooms 30 years before. "You fend for yourself on the field," Chappell says. "Nobody held my hand or walked me through my paces. On the field you have to read the signs and pick up clues to survive. It's the same in the dressing room. It's a tough environment. Right or wrong that was the way it was."

Hotel bars weren't a nightly stop-off for Chappell, but Rod Marsh was unofficially in charge of the pastoral care. "I've heard the laments that people didn't get much help," Chappell says. "Sometimes we went out of our way when a new guy was on the scene to offer a helping hand. With others we attempted it, but it didn't register what we were doing. By and large it was tough love. We got that from our parents."

The Chappells have supporters when they complain there's too much hand holding in the current game. However, the turnarounds after damaging setbacks of players such as Langer, Kasprowicz, Martyn and Hayden don't just show that the nurturing and management hugging works. It has been a world-beating success.

Matthew Hayden loves food so much he sometimes wants to cuddle it. A published cook and a quality fisherman, he is the recipe for an off-field SNAG. Throw in the Catholic chest-crossing and he is a proud, committed individual. Adam Gilchrist is similar: uncompromising and brutal with a bat; in love with his family and emotionally mature to cry out loud on the field or among his mates. Beneath a younger Southern Cross these traits were weaknesses. "There's a special uniqueness of individuals in the team now, and it makes for a good blend," Hayden says. "There are young guys, people with life experience, people with families and those values, and their cricket families. It's a great crock-pot of people."

|

|

|

It took Hayden three attempts to become a lasting part of the Australian dressing-room ethos. Helped by his supreme confidence and the public and private backing of Steve Waugh - hand holding's modern equivalent - Hayden has earned comparisons with Don Bradman. He instantly spots the differences between the current attitude and that of his first-class entry in 1991-92 and his South Africa Test debut three seasons later. "The young bloke gets a go in the dressing room now and it's a significant culture shift," he says. More serious barriers were torn down in the Proteas' homeland during the early 1990s, but Hayden pinpoints the period as the exit of other dusty and old-world ideals.

"It was a classic case of old school versus new school," he says. "That's what they called it - old school. Now it's different. Now most players are individuals and guys are allocated leadership roles, good roles. Old school was a different pot, but it was still a good one." Hayden says it's important to remember success has made the team "impossible happy". His post-match pizzas have filled team-mates' stomachs, but the newest-age minds have become so content that a couple of previous players admitted they wished they were born in the 70s and 80s instead of playing in them.

John Buchanan is a Chappell Era contemporary - he flirted with first-class cricket during a season with Queensland in 1978-79 - but believes not carrying "playing baggage" helped modernise the culture. He has loosened the border controls, opened up the thinking and changed outlooks with his dissemination of Chinese war tactics, laptop focus and experiments such as an on-staff yoga instructor. "The senior guys in my day were busy looking after themselves, which is why there were successful," he says. "Now we try to add another dimension, making them aware of other people."

This philosophy means Hayden can discuss steamed coral trout Thai-style with Justin Langer and offer everyone in the tour group a place on his rest day fishing or surfing adventures. Stuart MacGill can quiz Shane Warne about pinot noir labels instead of talking and drinking only top-shelf spin. However, Damien Martyn, who is enjoying the extra care on his second chance after his cruel dismissal in 1993-94, can still say his special talent is "just cricket" without worrying about the perceptions. The revolution also allowed Colin Miller a seamless rather than streaky entry into Tests with his side- and tradition-splitting hair colours and training creeds. In a twist, he was forced outside, but by his cigarettes rather than any internal smoke. "I was out of the room all the time," he says. "But I liked the time on my own because I'm actually a very shy person. The Australian team knew how I was because they knew me socially. I always felt comfortable."

Players are so pleased with the atmosphere that they look forward to touring and are unafraid to promote the love-in. When Brad Hodge was picked for the New Zealand trip he felt "welcomed in that environment". It's more management talk than heart-felt off-the-cuff, but at 29 and without a Test he believes there's a place for him. The importance of acceptance has been realised. "We want the assimilation to be a quick as possible," Buchanan says. "We want to make players feel part of the team. They may be part of the bowling group, the top-order batting group, the slips group, the inner-fielding-circle group."

Another reason for the shift was the response of young men who grew up in the dark days, shrugged or privately grumbled at the attitudes and vowed to do better with their responsibility. Damien Fleming was a scared first-gamer walking into the Australia dressing room of Border, Taylor, Healy, the Waughs and Boon. Unlike at Victoria, he felt at ease and was told to consider how he'd act when he became a senior player. "It was a very positive environment," he says. "You were showed a lot of respect and told to back yourself." Back yourself was a popular catchphrase of Steve Waugh and he was a central figure in making the dressing room mature. He wanted it to be a unit and, like most things, achieved one.

The current image is not fall-out proof. Things still go wrong occasionally and players go missing. Scott Muller is the obvious example of a peer-pressured scandal in the past decade, although Michael Slater, Matthew Elliott and MacGill have had public struggles with inner battles, lack of support and selection rifts. Muller came to Test cricket late at 28 with expanding business interests at XXXX, an outswinger at pace and a blond look more suited to Bells than Bellerive. "The Muller issue was a lot of things," Buchanan says. "It was a Scott Muller issue, a Shane Warne issue, a team issue, a public issue, a distance issue. It was a whole mix and it could have gone the same way anyway. Scott had great ability, but in the end I'm not sure he enjoyed the business of Test cricket."

Muller went back to Queensland for his emotional rehabilitation where the team embraced him, but a knee injury ended his first-class career in the same summer. "It should have been the pinnacle of Scott's career," a Bulls team-mate says, "but it became an experience that was clouded."

|

|

|

Others may have privately left through the cobwebs of the back windows above the urinals, but individuals are now cared for, tolerated, understood and celebrated. Michael Clarke knows he can plonk his bag down and race up to Ricky Ponting with an idea whether it's his first Test or 13th. The shame is that novices couldn't do the same in a pattern that burst through more than 30 years ago.

While Bradman's mighty success also brought him isolation, Brian Booth, the Australia captain dropped in 1965-66 so Ian Chappell could play his second Test, says there was no vindictiveness or targeting of players during his career. A devout Christian who wore God next to the coat of arms and spoke at churches on tour, he was the sort of individual who would probably have been singled out a decade later. "I wasn't victimised," he says. "People were always respectful to me and what I believed." Instead there were good-natured jokes and Wally Grout occasionally called him Gabriel in reference to the archangel.

Greg Chappell, the coach of India who was formerly in charge of South Australia, knows the tough love approach wouldn't work now and doesn't want it to. Sourav Ganguly wouldn't tolerate it for long. However, he believes the characters in Australia rooms are similar even if they aren't pinging 1970s sponsors' cigarettes at each other's bare feet. "There's a support structure now," he says, "but some guys still slip through the cracks."

The current method is modelled on respect and the cases of Watkins, Matthews, Yallop and Muller are unlikely to reappear because of the history lessons and the real-world management. Modern players are treated better whether their selections are freaky or fundamental. Brad Hogg and Nathan Hauritz have been surprising and controversial choices in the national side, but they were heavily backed and when Hauritz knocked over Sachin Tendulkar and VVS Laxman in November the cheers and back slaps of his team-mates were genuine.

Hauritz may have slipped to become a well-supported club bowler, but Hogg is Australia's No. 1 limited-overs spinner. The wild success stories are the length of Australia's Test and one-day batting orders; the old-world regrets grow. "There were too many judgmental people thinking Greg Matthews had a screw loose," David Gilbert, a friend for 30 years, says. "Greg was a prolific performer for NSW and all the things he gave to them he could have given to Australia. But it was too different, too difficult, too bad."

It's not only Gilbert who is certain the previous mistakes and mistreatment wouldn't happen today. From the outside the dressing room looks like a haven again. Hand holding works. New school is in.

This article first appeared in the July issue of Inside Sport

Peter English is the Australasian editor of Cricinfo