Colin Milburn - An Indomitable Spirit

Matthew Engel's tribute to boyhood hero Colin Milburn

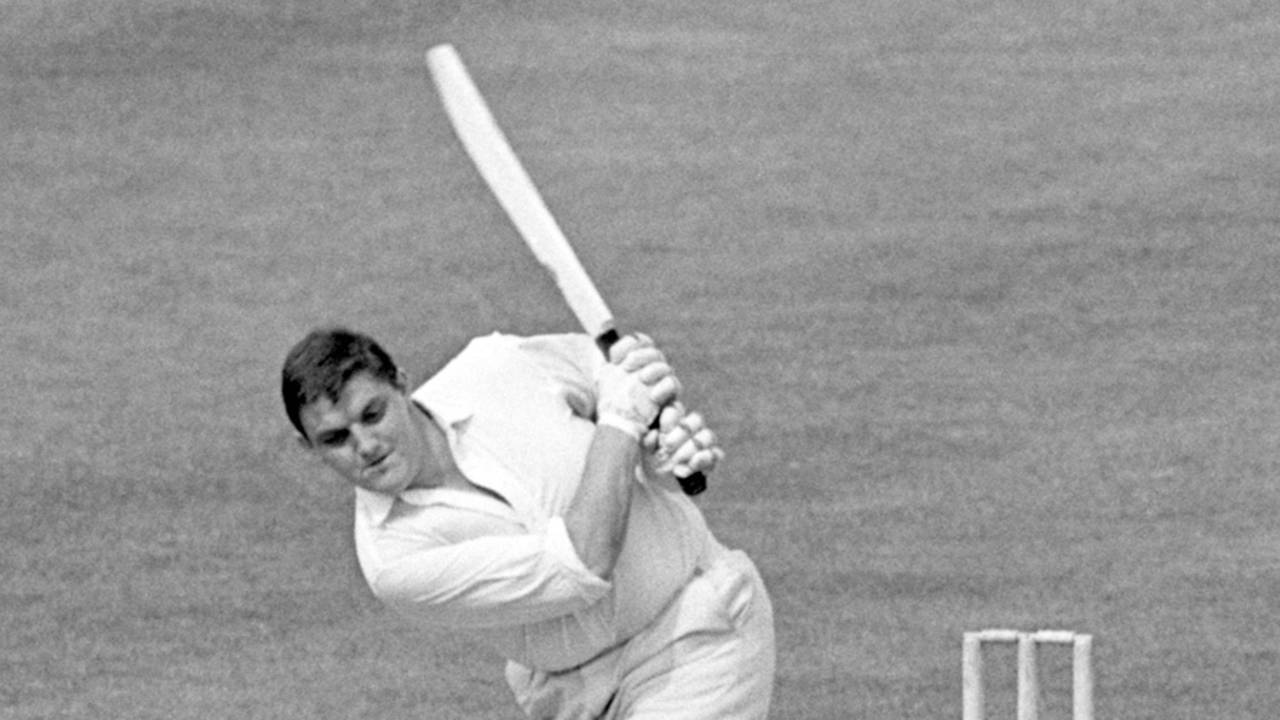

Colin Milburn in full flow • PA Photos

I do remember that the sinking-in process took longer than usual. Most of us were fooled a little: by inapt comparisons with Pataudi, who played on with his right eye gone; by the wave of hopeful Press coverage from the hospitals; by Colin's own quite outstanding bravery. I also remember feeling that if so freakish an injury (why couldn't he just have broken a leg like normal people, for Heaven's sake?) could end his career, then it was the saddest possible news for English cricket. Milburn might not have been the greatest cricketer of his generation, but he was, beyond question, the cricketer we could least afford to lose. And we lost him.

I was not and am still not an unbiased observer. Insofar as I ever grew up, I grew up, between bouts of boarding school, in Northampton in the 1960s. The Northants side of 1969 was not only good - we had the best and most exciting young batsman in England. What's more, he was a friend of mine. Well, more like a friend of a friend actually. But he would recognise me and pass the time of day and take an interest. It even fell to Colin to coach me at the Easter nets, which he did without losing his temper. I realised later that he was friends with pretty well everyone in Northampton. That turned out to be one of his problems.

Colin had arrived via County Durham because Ken Turner, Northants' secretary, had offered him 10 shillings a week more than Warwickshire. This transaction achieved slightly more notice than the acquisition of most young batsmen: Colin had achieved a sort of public notice as a 17-year-old schoolboy when he made 101 for Durham against the 1959 Indians. He even got a special mention in the Editor's Notes in the 1960 Wisden. He was, as Wisden put it, `a well-built lad' or, to put it another way, fat.

He had always been a tubby boy. In the cold winter of 1963, just as he was becoming established as a county player, he fought against it furiously and went down from 18 stone to nearer 16. Thereafter, though his weight was a regular talking point every April, I think it bothered him less. I often wonder how he might have batted had he slimmed down to fit the popular perception of what a cricketer should look like.

So often all his tonnage went into the shot. Yet I don't think there was anything essentially unconventional about his batting. Memory does odd tricks. I remember the crashing hook, of course; I remember the booming drive, hit most often past a helpless cover point; yet in the mind's eye I can most easily recall that great bulk leaning forward, ever so correctly, to prod away a ball he did not fancy. The difference between him and everyone else was that he would hit a 50-50 ball that anyone else would leave or block, and hit it with immense force. Not every time. There is another potent memory: his return to the old and grubby Northampton pavilion, red-faced and as near as he ever got to angry, after a daft nick to first slip when a single figures. For us kids, the day moved on to a lower plane. But the good days were electric, and if he got past 20, he rarely stopped before 70.

Years later, after the accident, I umpired a village benefit match in which he thumped harmless bowling all over the place for about an hour and I was able to watch at close quarters the visible signs of how he made up his mind what to hit. It occurred to me then that his secret had not been his bulk, nor his technique, nor even the quickness of his poor, damned eyes but the speed of his reflexes. How else could an 18-stone near-non-runner come to break the Northants catching record, which he did, in 1964, with 43 catches, almost all at pre-helmet short leg?

Those reflexes were never infallible. Nor was his judgment, and sometimes the good days were well spaced out. In 1965, he went into the final match still short of his 1000. Gloucestershire were at the County Ground and Northants needed to win to be champions. It rained on the first and last days, and the fact that Milburn made 152 not out in 3 ½ hours to get his 1000 made no difference whatsoever, except to soothe the pain. And the county still have not been champions.

But the blazing three-year summer of Colin Milburn's life was just about to start. The following year was the one in which many Championship matches had their first innings restricted to 65 overs. It was one of those early, faltering attempts to enliven the three-day game in response to the success of the Gillette Cup. Colin did not need livening up, but the system suited him very nicely. He began 1966 with two centuries in his first three innings, scored 64 for MCC against the West Indians, then made 171 at Leicester with Alec Bedser watching. On the Sunday he was in the Test team. D'Oliveira was also in the 12 for the first time (though on that occasion he did not play) and I remember being hurt and puzzled by the `Hello Dolly' headlines. Milburn did play and soon was being overshadowed by no-one.

Nine Test matches - that's all he had time for. He changed four beyond recognition, though it is true that England did not win any of them: a lively but chancy 94 as England went down to that very strong West Indian team, with Sobers, Hall and all, at Old Trafford on his debut; the 126 not out in the next Test at Lord's to save the game (only Colin would save a game by scoring an even-time century); the amazing, fighting 83 at Lord's against the 1968 Australians on a bad wicket; and the final 139 at Karachi the following year.

There would have been time for more, but the selectors kept dropping him. Barely a month after the 126 he was gone. He failed at Trent Bridge, then made 71 for once out at Headingley, but he was gone the next week along with Cowdrey, the captain, and half his team to make way for the Brian Close era. In that wonderfully vengeful mood that brings out the best in some cricketers, Milburn went to play for Northants at Clacton and scored 203 not out - a century before lunch, another before tea, and a new county first-wicket record with Prideaux. That year, Ollie was the first to 1000, scored the fastest century, hit the most sixes, and only missed 2000 because of a broken finger. There was no tour for him to be left out of, so he spent his first happy winter playing for Western Australia.

He played in two Tests in 1967, but his best score was 40 at Edgbaston. Nonetheless he scored the fastest century of the summer (78 minutes this time, four minutes quicker than the previous year) and was picked to go to West Indies. When he got there, he started slowly, lost out to Edrich for the First Test, and became a spare part.

It was clear that some influential people did not regard Milburn as a business cricketer. After his Lord's 83 the next year ended in a catch on the midwicket boundary, one of the selectors commented sourly, `What a way to get out.' He was injured after that and did not return until the Oval-D'Oliveira-Underwood-mopping-up Test, after which he was left out of the South African tour party. Since someone else was also left out, Milburn again found himself overshadowed by D'Oliveira, and there are plenty of people around who still believe Milburn's omission was the dafter.

But the curious thing was that Milburn had plenty of detractors in Northampton as well. He had loads of friends. In some cases the same people were in both categories. The County Ground crowds, such as they are, on both the football and cricket sides have long had a fairly well-deserved reputation for sourness. I think the town was much happier when 1965 was over and its team stopped all this winning nonsense; we could all go back to being happily miserable again. And much of the moaning was at Milburn. There was something not right about all that boozy joviality. Why couldn't he settle down and live and play boringly like you are supposed to do? And poor old Ollie did not seem able to shut them all up by going out and playing one of his really great innings. They always seemed to come somewhere else, somewhere exotic like Lord's or Clacton. Northampton had to be content with some very, very good ones.

Perhaps the greatest of all came that November, even further away. On a fearsomely humid day at Brisbane, Milburn went out to open the batting. At lunch he was 61 not out and, rather out of character, complaining; there was so much sweat seeping through his gloves that he could hardly grip the bat. After lunch, the weather cooled a fraction; Milburn went berserk. In the two-hour afternoon session he scored 181. Even Bradman never approached that. He was out the over after tea for 243 and apologised to his team-mates.

He was on a Perth beach with (so the story goes, and it is almost certainly true) a couple of birds and a good many beers when, three months later, he got the message that England needed him to reinforce the party for the substitute tour of Pakistan. It is generally held among cricketers that Perth is a better place to be than Dacca, and the feeling among the England party at that stage of the tour was, by all accounts, that they should fly out to join Milburn rather than the other way round. But he flew in via one of the most convoluted routes in the history of aviation, and the team summoned up enough energy to give him a guard of honour at the airport and con him into believing that there was no room at the Intercontinental with the other lads and so he would have to stay in a dosshouse next to a swamp.

His very presence brightened the tour. When they moved to Karachi for the final Test, Milburn was picked and played his last, biggest and probably greatest Test innings, 139 on a dead slow mud pitch. As at Northampton, as with the England selectors, he was not wholly appreciated - the crowd were too busy rioting to take much interest. But, as the game was abandoned after the gates were smashed by the crowd, it was generally agreed that whatever else had gone wrong for English cricket that winter - and pretty well everything had - at least Milburn had now emerged as a genuine Test batsman, and not just a slogger.

Sunday League begins

The summer of 1969 marked the start of the Sunday League which, genuine Test batsman or not, might have been designed for Milburn's personal use. He began the season with 158 against Leicestershire and played his part in a Northants win over the West Indians. His selection for the First Test was now not even a matter for discussion. And then it happened.

I was a schoolboy still and cannot be certain that all the smiling pictures were not just a front for the camera. But the sister-in-charge said his manner never changed in his 11 days in hospital; the hospital management committee singled him out in their annual report (`his infectious good humour and indomitable spirit raised morale throughout the hospital') and in the years that followed I failed to glimpse whatever sadness lurked behind the mask.

Colin Milburn spent a good deal of the time (too much, said all Northampton) after his accident in his old corner spot at the bar of the Abingdon Park Hotel, always with a happy group, in shadow, but obviously not in sadness. Then, quietly and suddenly, he left Northampton and returned to County Durham. There were still booze and birds but no marriage and, for a man past 40, no obvious purpose. He did this and that. He went to the odd London do. He still smiled. We still chatted. He almost found his métier on radio. His occasional commentaries were shrewd and funny and generous, because he did not believe no-one else could play. His indomitable spirit did not only raise morale at the hospital; it lit up my youth.